ABSTRACT. Little is known about French Canadian traders who

explored the pays d'en haut northwest of the Great Lakes during the

French

colonial era and made the transition to the British regime after 1763. Using

Metis genealogy. Swan and Jerome identified some of these earliest traders along the Saskatchewan River. The family of Edward Jerome has lived on a farm in

northwestern Minnesota since 1878. Edward identified Francois Jerome as a

voyageur who engaged with La Verendrye to explore the "Sea of the West."

Francois was at Fort Bourbon west of Lake Winnipeg in 1749. After the end of the

Seven Years War and the fall of New France, an elusive French Canadian called

"Saswe" by the Indians and "Franceway" by the inland HBC traders pioneered the

earliest explorations along the Saskatchewan, leading the Montreal traders of

British background into the Northwest to take furs away from the HBC bayside

posts. Fur trade historians identified him as Francois Jerome, and Swan and

Jerome's archival research demonstrated there were three generations of Jeromes

on the North Saskatchewan River before they moved to the Red River Valley in the 1820s. These men married Cree women and were the ancestors of the Red River

buffalo-hunting Metis.

SOMMAIRE. On sait peu de choses sur les marchands canadiens-francais qui

explorerent le pays d'en haut, au nord-ouest des Grands Lacs, au cours de l'ere

coloniale francaise, et qui passerent au regime britannique apres 1763, A l'aide de genealogies metisses. Swan et Jerome ont identifie quelques-uns de ces

lointains marchands le long de la Saskatchewan. La famille d'Edward Jerome

vit dans une ferme du nord-ouest du Minnesota depuis 1878. Edward reconnait dans Francois Jerome un voyageur engage par La Verendrye pour l'exploration de la

"Mer de l'Ouest." Francois se trouvait a Fort Bourbon, a l'ouest du lac Winnipeg

, en 1749. Apres la Guerre de Sept Ans et la detaite de la Nouvelle-France, un

mysterieux Canadien-francais, appele "Saswe" par les Indiens et "Franceway" par

les negociants de la Baie d'Hudson, effectua les premieres explorations le long

de la Saskatchewan et guida les marchands anglais de Montreal jusqu'au Nord-

Ouest, ou ils disputerent aux postes de la Baie le monopole du commerce des

fourrures. Les historiens voient en cet homme Francois Jerome, et les

recherches d'archives entreprises par Swan et Jerome ont demontre qu'il y avait

trois generations de Jeromes avant leur depart pour la Rivicre Rouge dans les

annees 1820. Ces hommes epouserent des femmes cries et furent a l'origine des

chasseurs de bisons metis de la Riviere Rouge.

In order to trace the origins of the Red River Valley Metis, the authors used the genealogy of Edward A. Jerome, of Hallock, Minnesota, members of whose family have lived on their farm for over a century and have been in the Red River Valley since the late 1790s. Hallock is 20 miles from Pembina and the farm is located on the Two Rivers, a tributary of the Red River. The Jerome family can trace their paternal roots through the Canadian fur trade in Ruperts Land, although the ethnic designation of "Metis" has no legal status in the United States. Edward Jerome wanted to trace his ancestry, and various lines led him backwards to Jeromes who were the earliest ancestors from Quebec. Jerome discovered that he is a descendant of The Buffaloe, a Pembina Ojibwe hunter, and of his daughter who was the country wife of Alexander Henry the Younger; she was later baptized as "Magdeleine Saulteaux."3 We researched these ancestors to determine at what point they arrived in Red River, but also to trace Metis family lines as far back in time as possible to determine their origins in New France as well as their Aboriginal connections. What we discovered is that Jerome's father's line had been "Metis" for nearly 200 years.

Stereotypes of Native people take various forms, but often subtly suggest that Aboriginal history is based on oral history rather than archival research. The implicit message is that Native history is difficult to document and unreliable, so oral history is not as valid as written history; many historians privilege the written text over oral sources and ignore the problems of unreliable texts. The other problem is that not all families possess an oral tradition. While an oral tradition might be possible in some families, it does not work in many cases where family and community history has been ignored. Cultural memory is often repressed in the face of racism, where people are made to feel ashamed of their Aboriginal background and are taught to forget about their Native ancestors while promoting immigrant (European or Canadian) relatives who are acceptable in the dominant society because they are "white." This is particularly true in cases like Metis history in the United States, where the Metis descendants of the fur trade are not even recognized as Aboriginal. If they do not have Indian status with a particular band, they are not "Indian"; yet they often experience racism in local communities, especially if they look different from other people who are the descendants of immigrants. How do they offset the shame engendered from the cruelty of racism?

Edward Jerome encountered this repression of Metis history when he asked his father, Edward Jerome, Sr., about his background: His father told him to "forget it because it will never do you any good." When interviewed by a local historian in the 1980s, Jerome Sr. was reluctant to talk.3 Edward Jr. had been curious when his cousin Frank Jerome wrote to the Hudson's Bay Company Archives (HBCA) in London, UK, and found references in HBCA journals to Jeromes who were Cree interpreters along the North Saskatchewan River. Another cousin, Dorothy Jerome Kalka of Pembina, North Dakota, also researched family history in the Saint Boniface and Pembina Church records. Edward Jr. undertook genealogy research on various fronts and then in the 1980s and 1990s carried on the research into the HBCA in Winnipeg. Swan started to collaborate with him in 1991, and we have published several articles on ancestors from the Saskatchewan and Lake Superior areas, and produced Swan's doctoral dissertation: "The Crucible: Pembina and the Origins of the Red River Valley Metis."4

The intention of this article is to demonstrate that Metis genealogies can be followed up with archival research to produce historical family studies. This is an option for Aboriginal and Metis families where the oral tradition and stories have been lost or culturally repressed, or as a complement to existing oral histories. This methodolgy is also a challenge to the stereotype that Aboriginal history is only based on the oral tradition. Ethnohistorians using insights from anthropology and history have demonstrated that indigenous knowledge can also be based on the expertise gained from archival research. Jerome personally felt that it was important for him to document from written sources information about his ancestors; using his family insights into language and other cultural issues rounded out the picture. We feel this approach has been remarkably successful, partly because the Hudson's Bay Company in Winnipeg provides extensive documentation of the fur trade through documentary sources such as postjournals, account books, district reports, correspondence and maps. This type of research can answer historical controversies about such questions as the origins of the Metis outside of the Red River Valley. Although this ethnic identify was first articulated during the Fur Trade War in 1815—16, we wanted to document how the Jerome family moved to Red River, from where, and when? Who were these Metis ancestors and who were in the formative generation of French Canadian voyageurs and Native women? Can they be named?

Edward Jerome identified Francois Jerome as the earliest voyageur from Quebec who was in the North West during the French regime and made the transition to the new fur trade in the British regime as a trader after 1763. There were several generations of Jeromes on the Saskatchewan River before they moved south in the 1820s. While it is difficult to identify exactly who was the first Metis in this family, our research showed that it is possible to trace the family and their movements through the generations and to show how they developed as voyageurs, traders, interpreters, buffalo hunters, and later as Red River Valley settlers.

French Canadian voyageurs did not always move directly from Quebec to the North West. As Jacqueline Peterson pointed out, communities of mixed ancestry people grew up in the Great Lakes region, especially at major trading centres like Detroit, Michilimackinac and La Baye (Green Bay, Wisconsin, on Lake Michigan).5 As the Great Lakes trade was developing in the 1700s, fur traders from Quebec also penetrated the Western Plains, looking for the North West Passage to the Orient, and more specifically the mer de l'ouest. Indian reports suggested a large, inland body of water which French explorers hoped would lead them to a river running west to the Pacific Ocean and an easy sailing route to China.6 The La Verendrye men found that there was much confusion over the geography of the interior of North America.7

The family of Pierre Gauthier, Sieur de la Verendrye, led and organized these early French explorations of the interior of North America, opening up the area west of Lake Superior, called the pays d'en haut (the upper country, or, in English, the North West).8 The goals of the fur trade and exploration sometimes conflicted. The French government and colonial administrators in New France wanted to know the potential of the western side of the continent for economic development, but did not want the expense of subsidizing the expeditions. To finance their explorations, the colonial administrations of New France encouraged Pierre Gaulder, his sons and their engages (voyageurs), to trade with the local Indians. The Sieur de la Verendrye undertook the fur trade cautiously, but had the genius to establish a string of posts along the interior waterways which could provide food and support for his explorations because it was too far to return to Quebec each fall. He thus pioneered the system of wintering in the interior which made the Montreal-based fur trade possible. The posts they built included Kaminisdquia at Thunder Bay, Fort St. Charles on Lake of the Woods in 1732, Fort Maurepas on the southern edge of Lake Winnipeg in 1734,9 Fort Rouge at the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine in 1737, and Fort La Reine on the Assiniboine near present-day Portage la Prairie in 1738. After the father Pierre retired in 1742, his sons continued his work by establishing Fort Bourbon on Cedar Lake, at the entrance to the Saskatchewan River west of Lake Winnipeg, and Fort St. Louis (Fort a la Corne), near the forks of the Saskatchewan River, several years before the fall of New France (1763). As Gerald Friesen noted:

This chain of posts was designed not only to control the highways of the fur trade and to protect the most effective route to the Rockies and the western sea, but also to cut directly across the flow of furs to the English on the shores of Hudson Bay. Thus, the competitions between French and English intensified once again. As was the case at the close of the preceding century, the French won the lion's share of the trade.10

As a result of these interior posts, the French were able to intercept Cree and Assiniboine middlemen before they took their furs to Hudson's Bay, and traded with them along the fringe of plains and parkland, so that the transportation of furs and goods was undertaken by the French rather than the Indians. Through loss of furs, the Hudson's Bay Company traders in their bayside posts realized that Canadian competition was cutting into their business, and they began sending young men westward with their Indians to gather intelligence about the competition and to recommend new methods of dealing with the Canadian "pedlars," as they called them.

The fur trade was a lucrative business, but it also became dangerous when the French allied themselves with the Cree, Ojibwe and Assiniboine against the Dakota/Sioux. The newcomers were drawn into traditional tribal alliances and Indian warfare, which often prevented the easy flow of goods. Eldest son Jean Baptiste La Verendrye lost his life along with Father Aulneau on June 8, 1734, at Lake of the Woods when the whole expedition was killed by the Sioux "as a penalty for having armed the Indians of his command against the Sioux in 1734."11 The father had sent his son to live with the Cree to learn their language and customs, and the French explorers and traders continued this practice as good communication with their allies and customers was a priority.

To undertake these great Journeys to the west, La Verendrye recruited young men from Quebec who paddled the canoes for his expeditions and carried out the labouring jobs of the posts where they wintered. According to voyageur contracts in Quebec notarial records, Francois Jerome, the son of a French militia officer by the same name, was one of these young men. His father's whole name was Francois Jerome dit Latour dit Beaume, who had come from Brittany to Montreal in 1698 and married Marie-Angelique Dardennes in 1705 in Montreal.12 They had 13 children, including two sets of twins; the eldest son, Francois Jr. was born in August 1706. After 1718, the family moved to the parish of St. Laurent on the island of Montreal.13

Francois Jr. first engaged for the West in 1727, his voyageur contract vaguely stipulating that he was engaged by M. De Villiers to make a trip to the pays d'n haut.14 The exact destination was not named. On October 12, 1733, he married Marie-Denise Denoe dite Destaillis. His mother-in-law was Jeanne Adhemar, a sister of the Royal Notary. Her father was Antoine Adhemar de Saint-Martin, and his son, Jeanne's brother, succeeded him to the title; Jean Baptiste Adhemar became Royal Notary in 1714, and he was Francois's uncle by marriage. The prestige of being married to the Royal Notary was passed down through several generations of Metis families in the North West, along the Saskatchewan and into Red River, as various descendants used the label "dit St. Martin" or "St. Matthe," corrupted in English as "Samart".15

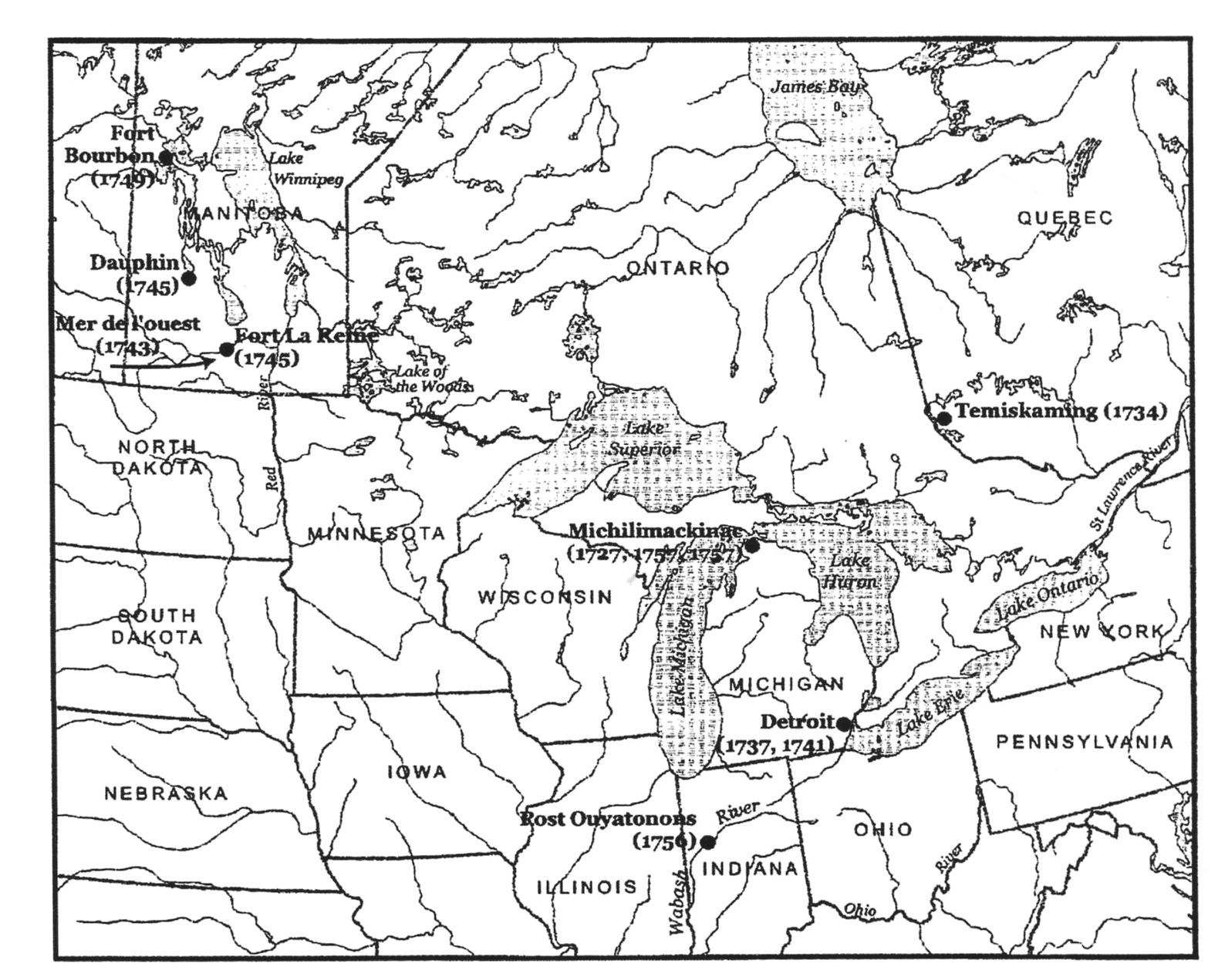

Francois Jerome and Marie-Denise Denoe had eight children, baptized in Montreal between 1735 and 1746; the five boys and three girls were registered in the parish of Notre Dame de Montreal. Two died as infants. In the genealogy of Tanguay, however, there are no continuing descendants of this line, although there are listed descendants of some of Francois's brothers, Nicholas-Charles and Jean Baptiste.16 This is perhaps an indication that Francois's male descendants moved out of Montreal, most likely because of the fur trade. Francois's career as a voyageur and later a trader continued from 1727 to 1757 (see Figure I for the geographical extent of his contracts). In the 1730s, he was appointed to the French post at Detroit, south of Lake Huron.17 The father, Pierre Gauthier, Sieur de la Verendrye, had retired in 1742, but his sons were carrying on his exploration work.

Figure 1. Fur trade voyageur contracts for Francois Jerome, 1700s.

Note: Modern provincial and state boundaries are included for reference.

Source: Rapports de l'Archivist du Quebec.

Cartography by Douglas Fast, University of Manitoba.

In 1743, Francois Jerome made a contract with the "Sieur de la Verenderie" {sic] to go to the Sea of the West.18 In 1745, Francois was hired by the Sieur Maugras to go to Forts La Reine and Dauphin in the same vicinity as the famous sons.19 Fort La Reine was located on the Assiniboine River near Portage la Prairie, and Fort Dauphin was between Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipegosis. In 1749, Francois Jerome had a contract for Fort Maurepas20 and Fort La Reine on the Assiniboine.21 Both these forts had been established by the La Verendrye family, as they were located on strategic waterways which connected with Manitoba Lakes that led to the northern reaches. In 1756, Francois Jerome dit Latour contracted to the Sieur Louis Lamay Desfonds to Aposte Ouyatonons, the Wabash Post in the Illinois country southwest of Lake Michigan." The following year, he must have made enough money to hire his own voyageurs and thus became a trader himself: "Sieur Francois Jerome dit Latour" hired Joseph Beaumayer and Gabriel St. Michel to go to Michilimackinac.23 This suggests that the latter French post on the Michigan shore between Lake Michigan and Lake Superior was now Francois's base of operations and that he may have stopped returning to Montreal each season.

If a trader wanted to penetrate the forested interior beyond Lake Superior, he had to establish a base in the Great Lakes and arrange to have the goods brought from Montreal; then when the furs came out, a Montreal crew would return with them. The voyageurs from Montreal were called "mangeurs de pore" (pork- eaters). The North West voyageurs in the interior were known as the winterers; although their diet at the posts consisted mainly of fish and meat, or pemmican, the canoe brigades ate Indian corn and wild rice traded from the Indians. The Canadian companies used the model of La Verendrye to organize posts at regular intervals to stockpile food, as the voyageurs did not have time to hunt and fish on their long journeys. Men like Francois, who organized the trade and supervised the voyageurs, were called "wintering partners" and they had the support of Montreal merchants and financiers who organized the trade goods to go to the Great Lakes as well as the selling of the furs in Montreal and Europe. The pioneering efforts by the La Verendrye family and the Great Lakes traders like Francois Jerome dit Latour, who obviously learned a great deal when he worked for them, developed the extensive Montreal-based trade network which culminated in the North West Company, which spanned the continent to the Pacific and the Arctic Ocean by the 1790s. Obviously, when British partners became involved in the Canadian companies after 1763, they did not have the expertise and depended on the experience of their French traders and voyageurs to keep pushing north and west to the finest fur fields of the Athabaska. Generally, anglophone historians like A.S. Morton emphasized the British leadership of the NWC after 1763, and little is known of the French traders and voyageurs who continued to work for the Canadian concerns after the fall of New France.

The sons of Pierre de la Verendrye continued with the fort-building north of the Assiniboine and west of Lake Winnipeg. Between 1741 and 1743, Pierre Gaultier de La Verendrye (second son of Pierre Sr.) built Fort Dauphin, near Lake Winnipegosis, while other members of their group built Fort Bourbon to the northwest of Lake Winnipeg, and Fort Paskaya (The Pas) to the northwest of Cedar Lake.24 Francois Jerome may have been involved in the establishment of the posts west of Lake Winnipeg. Jerome became associated with the La Verendrye family in 1743 when he signed a contract to explore for the mer de l'ouest, and later in 1745 with the Sieur Maugras for Forts La Reine and Dauphin.

The Sieur Pierre Gamelin Maugras was the cousin by marriage of Louis Joseph Gaultier de la Verendrye, also known as Le Chevalier, Louis Joseph Gaultier (the fourth son of Pierre Gaultier de la Verendrye and Marie-Anne Dandonneau)25, so it appears that Jerome was most closely associated with this member of the famous family. Le Chevalier had spent from the spring of 1742 to July 1743 exploring the plains south-east of Fort La Reine, looking for the "Sea of the West." According to his biographer, Antoine Champagne, he was accompanied by his brother, Francois Gaultier du Tremblay, two Frenchmen, and some Indian guides. Although Francois Jerome was engaged to explore for the Sea of the West in 1743, it is not clear whether he accompanied the La Verendrye brothers in 1742—43.26 This trip greatly increased geographical knowledge of the central plains, and also proved there was no Sea of the West in that area: the large body of water described by the Indians was probably Lake Winnipeg.27 Before he died. La Verendrye Sr. decided to focus his explorations on the north and the Saskatchewan River.

The governor of New France, Charles de Beauhamois, had a master plan to extend French control of the west; but it suffered from the vagaries of French politics and the explorers had trouble getting the financial support they needed. Pierre Sr. had been replaced as commandant for the poste de l'Ouest in 1743 while his sons stayed in the west:

In 1747 [Beauhamois] sent Pierre and the Chevalier [Louis Joseph] de la Verendrye to carry on the trade of the Western Posts, doubtless hoping that the Court would relent, as indeed it did and reappoint the father [Pierre as commandant]. The sons spent the winter at the northerly posts facing the English. In the spring of 1749, the Chevalier ascended the River Saskatchewan [Paskoyac] probably from Fort Bourbon, to the confluence of the north and south branches "where (there] is the rendezvous every spring of the Crees of the Mountains, Prairies and Rivers to deliberate as to what they shall do—go and trade with the French or with the English." That year the French carried off the main part of the trade in small furs at the expense of York Fort.28

In the late 1740s the sons stayed in the west, while their father tried to raise more capital for their exploring projects and their men continued to pursue the fur trade and take furs away from the English on the bay. Unfortunately, Pierre Sr. died in December 1749 in Montreal while his sons were recalled to Quebec for various military engagements.29 It is generally assumed by historians that when the French officers were recalled to New France to defend it, everyone left and the French lost the colony in 176330; little is known of the French traders who worked with the military and who were taking the furs away from the HBC.

When Jerome went to Fort Bourbon in 1749, he was not a soldier like the La Verendrye brothers but a voyageur and trader. In May 1749, the master of York Factory received a letter from Francois Jerome, asking for a list of prices and proposing a little commerce cache, or private trade. The French trader also showed his wisdom based on experience in dealing with the Natives:

As it came to our knowledge by the bearer of the said letter that you was ready to send one of your men in those parts, you may do it with all safety and fear nothing on our side. Leave the Indians quiet as we do. Although we have an officer with us. If you have any money. Goods or otherwise, we might settle a little private trade. Send us word at what price you take Beaver...

He sent along his broken oboe with the Cree middlemen, asking that it be repaired by the blacksmith at the fort: "I send by the Bearer of the Letter a Hautbois to get mended and in so doing, you will do me a sensible pleasure. You will give it to the Bearer of the Letter, and I shall have the Honoour to send you the payment next year or bring it myself.31 Historian A.S. Morton noted that this was the "First evidence of the plaintive reed by the shores of a western lake."32 John Newton, the master at York, dismissed the French trader's proposal, but copied a translation of his letter in his journal; the original must have been in French.33

In the early 1750s, the HBC masters at York Factory were so concerned at the threat to their trade that they began sending young men back with the Cree traders to explore and gather information about the Canadian traders, the "pedlars." Anthony Henday left York Factory in June 1754 and travelled along both branches of the Saskatchewan, reporting on the vast buffalo herds and resources of the plains. He also learned that the Cree and Assiniboine were middlemen in the trade, gathering up the furs of the Blackfeet who did not want to make the long trip to Hudson's Bay.34 Gerald Friesen described the problems that Henday encountered in getting the plains furs back to York:

But when his party commenced the long journey toward York, their sixty newly built canoes heavy with the furs they had gained in trade, they did not breeze past the French posts as Henday had hoped but rather stopped at each one for a little relaxation. At Fort la Corne,35 for example, "the master gave the natives ten gallons of adulterated brandy and has traded from them above one thousand of the finest skins." The story was repeated at Fort Basquia, and when the flotilla reached Hudson Bay in later June, many of the best and lightest furs had been left behind with the French...36

In one version, Henday described the French trader he met at Basquea (The Pas):

The Master invited me in to sup with him, and was very kind: He is dressed very Genteel, but the men wear nothing but thin drawers, and striped cotton shirts ruffled at the hands and breast. This House has been long a place of Trade belonging to the French, and named Basquea. It is 26 feet long; 12 feet wide; 9 feet high to the ridge ... and divided into three Apartments: One for Trading-goods, one for Furs, and the third they dwell in."

Geographer A.J. Ray noted that the only reason the Cree and Assiniboine made the arduous trip to the Bay, according to Henday, was to get Brazil tobacco from the English traders.38 Henday had complained in his journal: "It is surprizing to observe what an influence the French have over the Natives; I am certain he hath got above 1000 of the richest skins."39

Friesen also contends that the problems arising from French competition were not communicated to the London Committee, who only saw an "expurgated version of Henday's full journal, and his information was not acted on for another two decades."40 Presumably he is referring to the establishment of the first HBC post in the interior, Cumberland House, established by Samuel Heame in 1774.41 The York masters continued to send out exploring expeditions which brought back information about the French pedlars in the 1760s and 1770s, involving people such as Joseph Smith, Joseph Waggoner, Isaac Batt, George Potts , Henry Pressick, William Pink and Mathew Cocking. A.S. Morton noted that nine voyages were made into the interior from 1754 to 1762.42

Francois Jerome was obviously part of these early French trading operations along the Saskatchewan, and he gained valuable experience about the logistics of the trade without having to deal with the politics of the French court and colonial adminstration like the La Verendrye family. The French traders saw an opportunity when the war in New France called their officers home, and they took advantage of the lack of colonial control to continue their Indian trade on the strategic Saskatchewan route. Encounters documented in the HBC journals by the inland British visitors suggest their continuing presence, although Canadian historians have largely ignored them. The fact that HBC men kept journals that have survived meant that explorers like Anthony Henday were extolled while the French traders were almost invisible.43 Morton observed this contradiction more than most:

The Frenchmen remaining at the posts were little more than voyageurs and clerks long in the trade. Among them, probably, were Louis Menard at Nipigon, the elusive Francois on the Saskatchewan, and perhaps a Blondeau at La Reine. One by one the posts were abandoned, no doubt for lack of goods. La Reine was still open in the winter of 1757-58, when Joseph Smith was on the Assiniboine. In the spring Fort Bourbon was burnt. It was not reoccupied. In 1757, La Gome's Fort St. Louis was closed; in 1759, Fort Paskoyac. That summer a Frenchman named Jean- Baptiste Larlee came down from this last post to York Fort to seek employment. He was sent off to England... He reported that ... Frenchmen were building where Henday had proposed that the Company should open a post (at Moose Lake). By 1760 all the French posts on the Saskatchewan were closed.44

It seems unlikely that all the French military posts closed by 1760, because some of the traders stayed in the west When HBC man William Pink encountered the French pedlars in the spring of 1767, the Indians told him that the Canadian houses had been on the Saskatchewan for at least ten years, i.e. 1757, before the end of the French regime. Francois Jerome had been sent to the Wabash River in Illinois country in 1756; but at that time the trade became free and he hired his own men at Michilimackinac in 1757 and returned to the Saskatchewan.45 Morton reports a story from Fort Bourbon in 1757, when HBC trader Joseph Smith met the French master over a pot of brandy. The French leader questioned his guest about their involvement in the Seven Years War and whether the fur traders should allow military conflicts to interfere with the trade: "What if the King of England and the King of France are att {sic] war together, that is no reason why we should, so Lett us be friends."46

The Elusive "Franceway"

It was a long way back to Montreal and it was probably around this time that the French traders started using Michilimackinac and Grand Portage as rendezvous points47 so that they could take their furs out in the spring and return with their Canadian goods before the cold weather in October.48 After the Seven Years War ended, there was no official sanction for interior trading and no licenses granted until l767.49 After working west of Lake Superior since 1743, Francois Jerome had acquired knowledge of local Indian customs and of the Cree language, which helped him pursue a successful trading career. By 1757, he was in charge of his own crews and continued his role as a wintering partner for another 20 years along the Saskatchewan.

There is some disagreement in the literature about when the first Canadian traders entered the North West after the end of the war because trade licenses were not issued until 1767. However, contemporary documents hint at an illegal trade before licenses were authorized. W.S. Wallace observed that the Moose Factory journals from James Bay reported that Indians had seen the Canadians since 1761.50 A.S. Morton noted that Benjamin and Joseph Frobisher wrote to Governor Haldimand that the first trader from Michilimackinac to the interior was reported in 1765. He asked rhetorically:

There were men, then, who snapped their fingers at the Regulations, and from 1765 slunk through into the North-West. Who were they? The historians must now put on the mantle of Sherlock Holmes, point out the delinquents, and track them to their lair.51

The use of his language suggests colonial dishonesty, rather than entrepreneurial competitiveness. W.S.Wallace identified "Franceway" (surname not mentioned) as the first master pedlar to reach the Saskatchewan in 1767. HBC explorer William Pink saw Franceway's buildings near The Pas in the spring; but the French were not there, possibly having already left for the Great Lakes rendezvous.52

In 1767, there was a license issued to Francois Le Blanc (printed as "Blancell"). In the fur trade returns for 1767 at Michilimackinac, Le Blancell was listed as being financed by Alexander Baxter of Montreal to take six canoes to Fort Daphne (Dauphin) and La Pierce (Portage La Prairie or Fort La Reine), valued at 2,400 livres. This was the largest consignment of goods that year; the next highest value was 1,106 livres to Louis Menard, financed by Forrest Oakes.53 "That Francois LeBlanc was handling business (for himself or for others) in a large way is shown by the value of his cargo," muses Morton.54 LeBlanc as a name then disappeared from the records, but genealogists suggested that this was a surname used by the Jerome family.55

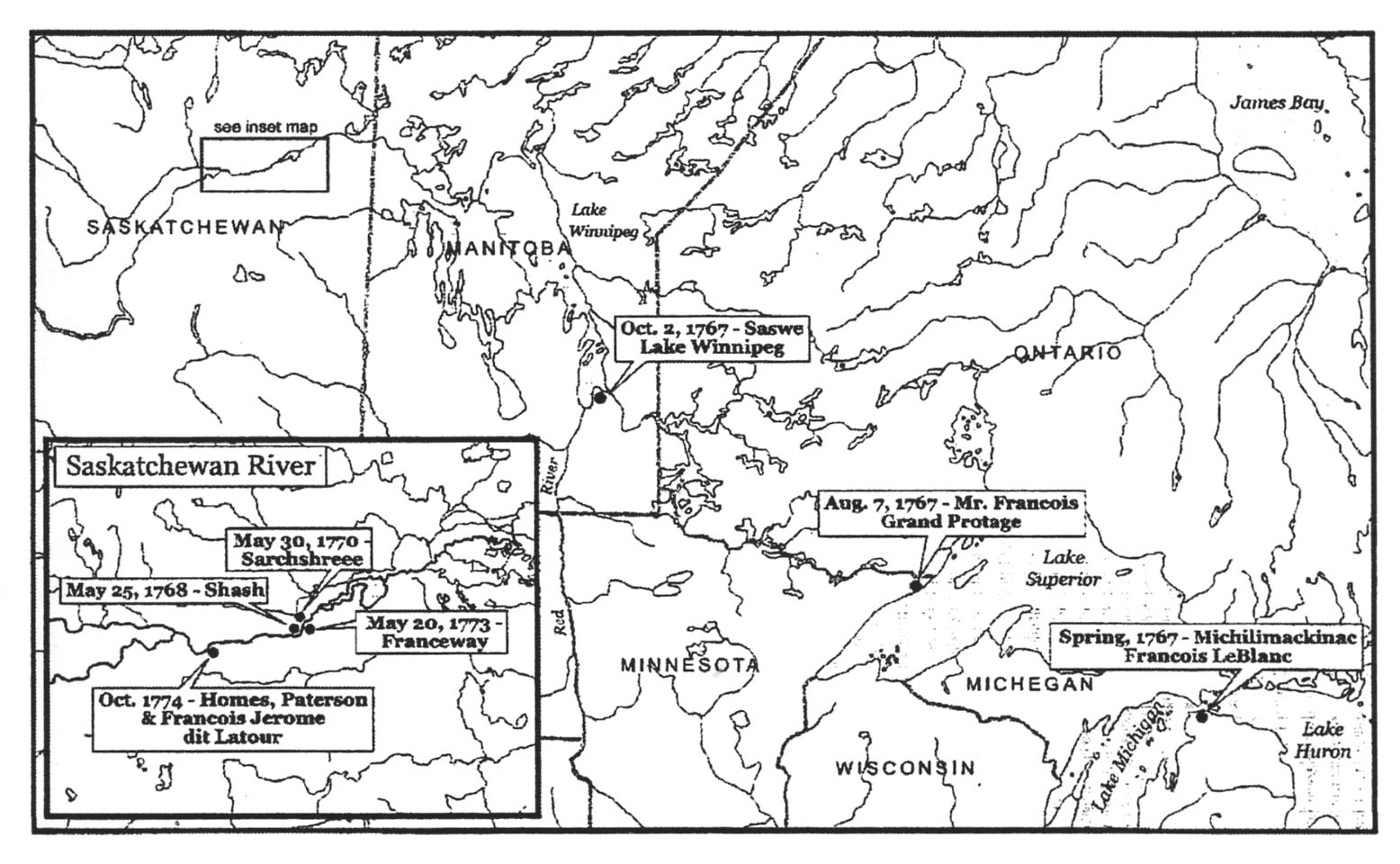

A number of the HBC traders sent inland encountered a man known to them as "Franceway" or by his Indian name, "Saswe," or a variant of it from 1767 to 1777. This figure has remained somewhat mysterious because no surname identified him, but circumstantial evidence suggests he was Francois Jerome who had been at Fort Bourbon in 1749. Figure 2, tracing Franceway's movements between 1767 and 1774, suggests that Francois LeBlanc of Michilimackinac, Franceway and Saswe were the same person. For example, in August of the same summer, British explorers Captain James Tute and Jonathon Carver met "Mr. Francois" at Grand Portage when the Michilimackinac commander Robert Rogers sent along messages with the trader to the starving expedition.56

Figure 2. Reports of Mr. Francois, Saswe, Franceway and Francois Jerome, 1767-1774.

Cartography by Douglas Fast, University of Manitoba.

A month later, William Tomison had come inland for the HBC from Fort Severnon Hudson Bay coast. He did not meet Franceway himself, but observed the Canadian traders on Lake Winnipeg who threatened British trade on September 3, 1767:

Arrived at the great Lake [Lake Winnipeg] where I found many Indians, waiting for the arrival of the English and French pedlars. They informed me that there were two Houses at Misquagamaw [Red] River within 2 days padle across the Lake.57

This suggests the first documented penetration of Red River since La Verendrye, but it is possible that Canadian traders like Jerome, Charles Boyer and Forrest Oakes had used it before they were observed by the HBC. Tomison also commented on the variety of goods the Canadian traders were bringing into the interior:

they take all kinds of furs, the natives were cloathed in french cloth, blankets , printed callicoes and other stuffs ready made-up and many other sorts of trading goods, their tobacco is white and made up in rolls and brinks, their guns are lightly made.58

He was "humiliated" to find that he could not prevent the Indians from selling their best furs to these Canadians.59

A month later, in October 1767, on Lake Winnipeg, Tomison met a French trader with ten Frenchmen and fourteen Indians in six large canoes on their way to The Pas, west of Lake Winnipeg, and identified the leader as "Saswe." This was two months after "Mr. Francois" left Tute and Carver at Grand Portage. Tomison complained that Saswe refused to talk "Indian" with him. Perhaps this is because the French trader chose not to give out information. Intelligence gathering on the opposition was an important rule for inland men: HBC inland traders were instructed to gather intelligence about the competition, and Saswe may have been reluctant to divulge his destination. Tomison learned through an interpreter that Saswe was financed by a Frenchman in Montreal and was not connected with the traders at Misquagamaw (Red) River. He described Saswe as follows:

his dress was a ruffled shirt, a Blanket Jacket, a pair of long trousers without stockings or showes, his own hair with a hatt bound about with green binding, a poor-looking small man about 50 years of age, he seemed to have a great command over the men, he lay in the middle of the canoes with his wife and son, each of these canoes carie about 3 tons, his Indian conductor guide padled in a small canoe with his wife who was dresed {sic] very fine, when the wind favoured, they have a square sail which helps them greatly.60

Tomison's description provides details of the material culture of the French Canadian traders coming into the North West after 1763. Francois Jerome was born in 1706, so in 1767 he would have been 61; but a man doing this kind of hard travelling twice a year would have been in good physical shape, even if he was not paddling the canoe like a voyageur. "The "poor-looking" comment suggests that he was not ostentatious, but dressed for practicality, like the Indians. Instead of Canadian shoes, he probably wore moccasins made by his Indian wife. The "blanket jacket" refers to the typical Canadian voyageur capote made from a blanket. The reference to the family suggests he had an Indian country wife (she was probably at least twenty years younger than him, since the son sounds like a child; if the son had been a teenager, he would have been paddling the canoe).

Saswe must have enjoyed the respect of his Indian companions as he commanded a large fleet of six canoes. Since he sat in the middle of the canoe with his family and was not paddling, he was in a higher social position than his men, suggesting that he was no longer a voyageur and had become a "bourgeois" or wintering partner. Since he had "great command over the men"—not a given in the social hierarchy of the fur trade—he must have had a gift for treating his men well and with respect, i.e., he was a good leader. After trading four bags of wild rice from Tomison's Indians, Saswe pushed on and did not stop at The Pas as he had told the HBC man, but continued to Pemmican Point on the Saskatchewan.

Although the HBC traders often underestimated their Canadian competition, Saswe was a successful trader who got along well with his French Canadian engages as well as his Indian customers, to such an extent that the bayside managers realized that they were losing about a third of their furs every season to these newcomers. William Pink, another HBC trader inland from York, passed the Canadian houses in the spring of 1767, also trying to get information on the Canadian traders for his master, Ferdinand Jacobs. The following spring of 1768, on May 25, Pink passed the house where "Shash" had resided.61 He was told that Shash was in partnershp with James Finley of Montreal, "the first British Pedlar of whom we have record on the Saskatchewan after the 'conquest.' He noted that the chiefest persons name is Shash, they are all French men that are heare upon the account that the English did not now the way.62 The following year, on May 16, 1769, Pink observed:

this day i came down to the plase whare the people of Quebeck ware staying as i went up heare i find the people belonging to this man ware not yet come up ... one English man with 12 Frenchmen with him, his name is James Finley from Montreal, he came up with three canewes.63

On Pink's fourth journey, on May 30, 1770, he noted that no Canadian canoes came up in the fall of 1769. He met a canoe with four Frenchmen who told him that "Sarchstreee" would be coming with four canoes; but that winter had come on too early and they had a good deal of goods taken, presumably by Indians. They had come from forts "at the Bottom of the Bay." Usually this term referred to the bottom of James Bay, but that was not on the Canadian route to the interior. Perhaps Pink misunderstood, and the French Canadians were referring to Traverse Bay at the bottom of Lake Winnipeg on the southeast side. The Canadian route through the Winnipeg River emptied into the lake at this point. Although there were no forts there in 1770 (the post farthest west of Lake Superior was at Rainy Lake), it was customary for the traders to meet the Indians (and vice versa) at the mouths of significant rivers, as Tomison had done.64 It would take 20 years for the Canadians to realize that it would be a good idea to have a provisioning post at this site (Fort Bas de la Riviere Winipic and Fort Alexander) where they could supply the canoe brigades with pemmican for their long journeys to the Athabasca.65

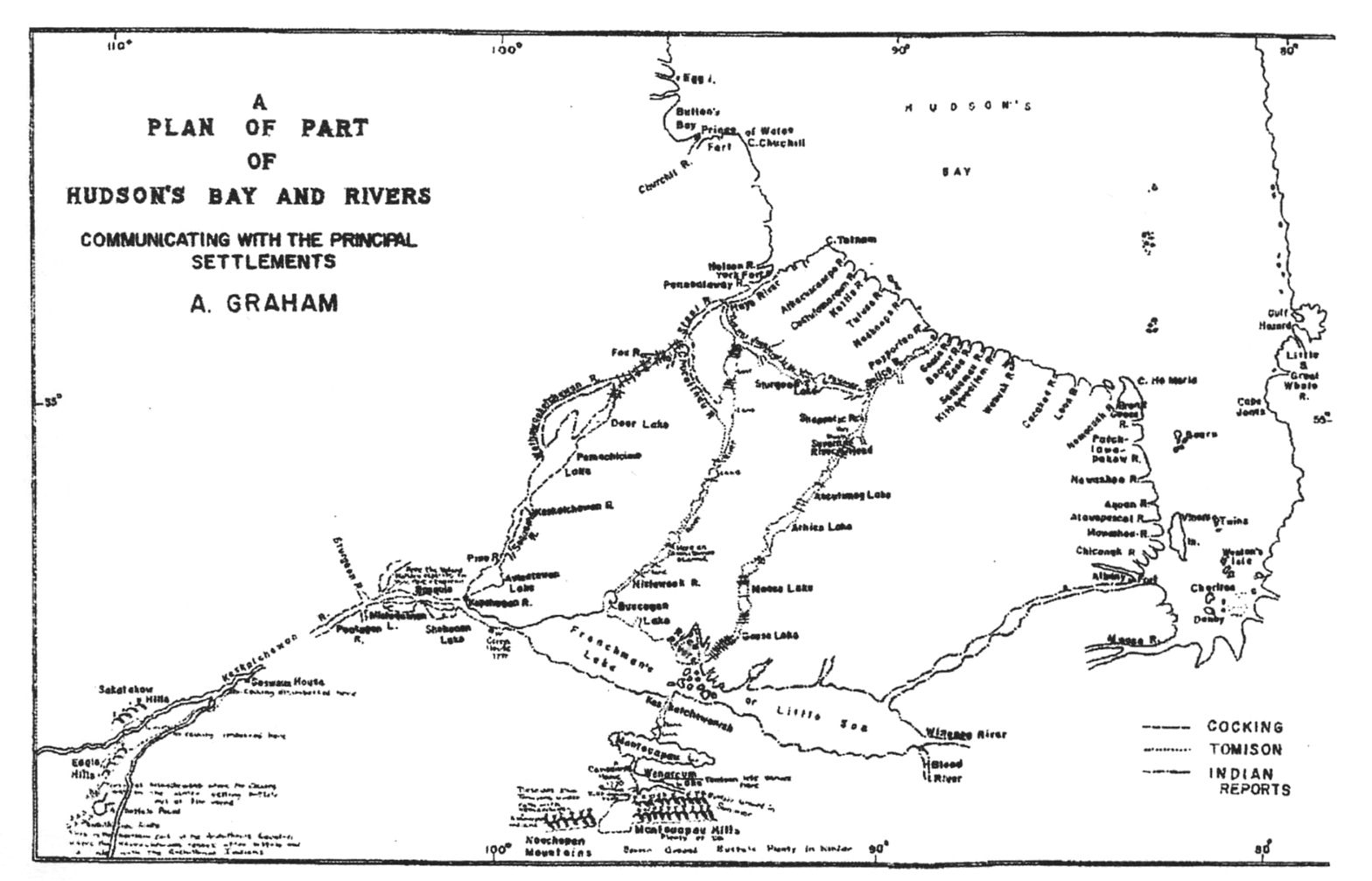

Figure 3. Saswaus House on Andrew Graham's map.

This map was prepared by R.I. Ruggics, from two original manuscripts (maps G.2/15 and G.2/17) in the HBCA, London. It was based on information received by HBC traders who were sent inland by Graham who remained at York Factory at the bay as well as Indian reports. Graham notes "Saswaus House" on the "Keskathcewan River" east of the fork in the Saskatchewan River. He notes: "Mr. Cocking disimbarked here." See John Warkentin and Richard Ruggles, Historical Atlas of Manitoba, Historical & Scientific Society of Manitoba, 1970: 94- 95.

To summarize the reports of this French trader. Figure 3 outlines his progress from the Great Lakes to the Saskatchewan. In the summer of 1767, Francois LeBlanc obtained the fur trade license at Michilimackinac. On August 7, 1767, Mr. Francois met Captain Tute and Jonathan Carver at Grand Portage, Lake Superior. On October 2, William Tomison met Saswe with six large canoes and fourteen Indians on Lake Winnipeg, claiming he was going to The Pas. On May 25, 1768, the following spring, on the Saskatchewan River, William Pink passed the house where Shash had resided and then visited the new post where he was partners with James Finley from Montreal. These reports apparently were about the same trader, a man well-known to the Indians along the Saskatchewan, who was the principal Canadian opponent of the HBC.

The third HBC trader who encountered the trader he called Franceway was Matthew Cocking, but before they actually met he received information about him from his Indian companions.66 For example, on March 4, 1763, Cocking heard from a young hunter that "Franceway had sent some of his Men through the Country among the Natives to collect provisions..." Franceway knew the importance of collecting country produce before the long winter. Later, he would use the same deployment, called en derouine, to send his men to the Indian camps to collect their furs without waiting for them to bring these furs into the posts. On March 17, 1773, Cocking observed that "several canoes are laying in places all the way down to the Pedlers principal settlement at the Grand Carrying Place." The Indians told Cocking that they were dissatisfied with Franceway's trading practices and threatened to take away his furs by force if he refused to comply with their demands. This may have been said only to impress the Englishman, because in fact the Indians liked the French traders and Franceway in particular.

On May 20, 1773, Cocking and his Indians arrived at Franceway's settlement and the trader greeted the Indians with a gift of four inches of tobacco. Cocking estimated that he had about 20 men with him. He described Franceway's trading post as follows:

Franceway's dwelling is a long square Log house, half of it appropriated to the use of a kitchen and the other half used as a Trading and Bedroom with a loft above the whole length of the Building where he lays his Furrs. Also 3 small Log Houses, the Mens appartments, the whole enclosed with ten-foot stockades forming a square of about 20 yards. His canoes are 24 feet long measuring along the Gunwhale, 5 quarters broad and 22 inches deep.67

Cocking complained about the way the Indians gave away all their furs for a low price and a gift of "spiritous liquors." Cocking was surprised that the Indians who had previously complained about Franceway were on such good terms with him and were willing to trade away all their furs. On May 21 "The Natives all owned and complained at their hard Dealing of Franceway and at the same time cannot account for their folly in expending their Furrs."

On May 22, 1773, Cocking accepted an invitation to dinner with Franceway and his country wife. The latter employed a translator, whom Cocking thought was an Irishman; but possibly it was Peter Pangman, whose New England accent might have been confused for an Irish one. Pangman later that summer travelled to York Factory to see if he could import his goods through Hudson Bay; but Cocking's superior, Ferdinand Jacobs, disabused him of that notion.68 What really bothered Cocking was that Francois allowed the natives and engages to come and go inside his house when they liked. "They never keep a watch in the night, his reason was that the men would not consent to any such order if given by him."69 In the hierarchical nature of the Hudson's Bay Company, there were social distinctions between officers and "servants," their term for the labourers, and social distances between the officers, men and Indians. Since the HBC had not yet moved inland, they were not used to dealing with Indians in their own territory. Keeping a distance between traders and clients of whom Cocking was somewhat afraid was an issue for him. Cocking was critical of Franceway's methods of dealing with the Indians, but this was more a reflection of his own prejudices than an objective assessment of the French trader's success. A.S. Morton saw through the pretence:

Cocking, with no goods, no rum, and but little tobacco, a stranger, with a great gulf—an English gulf—between him and the Indians, was helpless before this Indianized Frenchman.70

It was precisely the French traders' ability to live like "Indianized Frenchmen" that made them successful traders in the interior. As Thomas Hutchins at Albany Post pointed out in 1776:

The Canadians have great influence over the natives by adopting all their customs and making them companions. They drink, sing, conjure, scold with them like one of themselves and the Indians are never kept out of their houses whether drunk or sober, night or day.71

British traders like Hutchins and Cocking found the Canadians' egalitarian attitudes disturbing to their accepted ideas of the British class structure. Readers should therefore be cautious about accepting literally the judgmental attitudes of traders like Cocking, for example, when he called Franceway "an ignorant old Frenchman." He also mocked Indian rituals that they used to ensure good hunting and regarded their medicine as superstitious. On October 30, 1772, he observed:

Indians all employed looking after their Traps. The evenings are all spent in smoking and singing their God Songs, every Indian in his turn inviting the rest to smook and partake of a cold collation of Beries; this is done that they may be fortunate in trapping, live long, etc. Which they think has a great effect at the same time neglecting the only method of building many traps, most of them being very dilatory.72

Unlike Anthony Henday who enjoyed living with the Indians and made the most of their hospitality. Cocking depended on them to guide him in a foreign country , but at that same time acted judgmental and wrote critically—not a good way to ensure strong trading relations.73

Franceway understood the nature of fur trade rituals, immediately giving Cocking's Indians some tobacco when they arrived at his camp. Some of his Indian informants told Cocking that they had collected forty skins at the buffalo pound and sent them to Franceway expecting a supply of ammunition and liquor in return. Cocking was at a disadvantage because he only had Brazil tobacco, highly prized by the Indians, but few goods to trade. "But I know Liquor is the chiefest inducement which I find the Natives always go for to the Pedlers in the Winter."74

There were other references to Franceway/Saswe in the records of the fur traders. Now the inland traders were not just from York, but from other bayside posts, such as William Tomison from Severn. Moses Norton, master at Churchill, sent Joseph Hanson inland in 1773 to report on the invasion of pedlars. A.S. Morton writes:

Joseph Frobisher and Francois were on the Saskatchewan in the Frobisher-McGill—Blondeau interest... An old Canadian who had been upwards of 30 years among the Indians, had come in with three canoes equipped by one Solomon, a Jew from Montreal.75

Victor Lytwyn identified this French trader as Francois Jerome dit Latour, and his financial backer as Ezekial Solomon.76 A.J. Rae indicated that in 1774 William Holmes came into the Saskatchewan Country with Charles Paterson and Francois Jerome dit Latour, with seven canoes on their way to their post at Fort des Prairies (Fort a la Come, Saskatchewan).77 A.S. Morton found references to these pedlars in Samuel Hearne's Cumberland House Journal:

A month after Heame finished his log hut [at Cumberland House], the Pedlars came up the Saskatchewan on their way to their wintering grounds. The two Frobishers, Joseph and Thomas, and their partner, Charles Paterson, with Francois, in the company came... Their partner, Paterson, with Francois, was going up the Saskatchewan with 12 canoes and 60 men. These two, while in friendly association, were probably connected with different firms in Montreal—Paterson ... with the Frobisher- McGill partnership, and Francois with Finlay. Francois, as has been seen, had come inland the year before independently of Blondeau, but had entered into an arrangement and occupied what came to be called Isaac's House jointly with him... Thus, the Pedlars were on all the water-ways converging on Cumberland House.78

The fierce competition taught the pedlars that they were better off combining their interests and cooperating so that they could all profit while putting the HBC at a disadvantage.

In 1775, Alexander Henry travelled along the Saskatchewan with Paterson, Holmes and two Frenchmen (unnamed) which is odd because he was probably with the Canadians along the Saskatchewan. He did not mention Franceway, although the latter was still wintering in the area. Morton writes that

There was a Frobisher post somewhere beyond Lake Winipegosis. A Master along with Isaac Batt was to winter at some place to be agreed upon with the Indians.79

After 1784, the references to Franceway were less frequent; and they stopped by 1777, when Cocking reported Franceway had left the country after killing an Indian.80 He retired to Detroit, and his death date is unknown.81

To recapitulate, Francois Jerome dit Latour, the son of the militia captain in New France, went to the Great Lakes and pays d'en haut in 1727. By 1743, he was assigned to the La Verendrye party to explore for the mer de l'Ouest. In 1749, he was working at Fort Bourbon on Cedar Lake, on the strategic route linking York Factory with interior, and the competition of these Canadians forced masters at York Factory to send men inland to gather information about the competition and persuade the Indians to maintain their custom of trading at the Bay. Several of these men, such as William Tomison, William Pink and Mathew Cocking, encountered a trader named Franceway, Saswe, Shash, or Shashree. His surname was never mentioned and the only French Canadian who had a fur trade license out of Michilimackinac at this time was Francois LeBlanc. Genealogist Cyprian Tanguay suggested that the Jerome family used other surnames, such as Beaume/Beaune, "dit Latour," and LeBlanc. Both fur trade historians A.J. Ray and Victor Lytwyn argued that the famous Franceway, who was one of the earliest French Canadian traders up the North Saskatchewan and who had been in the country (according to Cocking) for thirty years, was Francois Jerome dit Latour.

The other piece of the puzzle is that there were Jeromes mentioned in fur trade records as living on the Saskatchewan River, in the area around Fort Carlton, for three generations after Francois before they moved to the Red River Settlement in the 1820s.82 Pierre Jerome/Gerome was an interpreter at Fort des Prairies on the Saskatchewan in 1799 and 1804.83 Similarly, when Alexander Henry the Younger moved to Fort Vermilion in 1809, he hired "Jerome" as his Cree interpreter.84 The fact that this man was working as a Cree interpreter suggests that either he had been living in the area for a long time or he had a Cree wife and children.

Pierre Jerome died at Carlton in 1821 and the officer in charge, John Peter Pruden, suggested that he had been "many years in the service of the NWC as Interpreter for the Crees and I should suppose he must be upwards of 80 years of age. This would put his birth at about 1740."86 At the same time there was at Fort Carlton a young Martin Jerome aged about 20 years old, but it appears that a Martin Jerome Sr. was between the generations of Pierre and Martin Jr. Martin Jr. listed his father as Martin Sr. on his marriage certificate; and his sister, Marie Louis Jerome, born in 1803, listed her father as Martin on her St. Boniface marriage record.

Henry's journal also suggests that the man he used as Cree interpreter was younger and more active. When he worked at Fort Vermilion in the winter of 1809-10, he worked en derouine collecting furs from the Crees: for example, September 19, "Jerome returned from the Cree camp, where there are 20 tents"; February 13, "I sent Jerome off en derouine to Mistanbois"; February 20, "Jerome and [La]Rocque cutting out pemmican bags"; May 21, "Jerome & the lads supply us with fish."87 Jerome also appears on Henry's census of 1809 with no wife, but with four children. On the June 3, 1810, roster of families we find that in 17 tents for Henry's men, Jerome and LaPierre shared a tent with 2 men, 1 woman and 5 children.88 These records suggest that Jerome had lost his wife and was raising the four children himself. However, only two of the four later showed up in Red River Settlement in the 1820s. Jerome's father was probably Martin Jerome Sr., who had no birth record in Quebec and was probably born along the Saskatchewan and lived there all his life.

In the North West Company Fort des Prairies Equipment Book of 1821, Martin Jerome, age 19 (born around 1802) has an account, showing him to be a "Native of Fort des Prairie," i.e„ born on the Saskatchewan; his good friend, Jean Baptiste Letendre Jr., was also listed in the account book. Called "Samart Gerome," Martin did some work for the master at Carlton House in 1821-22. For example: December 17, "Sent off Wm. Gibson and 2 half Breed young men with the packet for Dog Rump Creek"; January 30, "Samart Gerome and Battoshes Son [Letendre] arrived from Dog Rump Creek House, but brought no letters from Edmonton House"; June 5, "Mr. Monro, Samart Gerome, Beauchamps and Gausawap arrived with horses from Edmonton, 15 of which belonged to the Company [HBC] and 6 to private individuals."89 Chief Factor Colin Robertson at Norway House requested Pruden to have guides ready for his trip from Carlton to Edmonton in 1822, and suggested that "Jerome and the White Eagle's son are supposed to be the best guides."90

In the early 1820s, Martin Jerome Jr. became a freeman and moved to Red River Settlement with the Letendre family after the death of Pierre Jerome. He married Jean Baptiste's sister Angelique and is listed in many of the subsequent censuses.91 This migration to Red River by the Jerome and Letendre families paralleled the general movement of freemen and their families to the settlement, where they could raise their families close to schools and churches.92 These young men were thus typical of Cuthbert Grant's Metis cavalry: multilingual with French and Cree as their main languages, expert buffalo hunters, and plains traders with no ties to Quebec.

It is not possible to determine the exact relationship of Francois, Pierre, Martin Sr. and Martin Jerome Jr. (Samart Jerome). It appears that Pierre was born in Quebec, and Martin Sr. and Jr. on the Saskatchewan. Their mothers must have been Indian or mixed-blood, but their identity is unknown. The fate of Francois's Indian wife and child is also unknown. It seems likely that Pierre was the nephew of Francois Jerome dit Latour, the son of the latter's brother Pierre, born in 1718. A Pierre Jerome was married in Quebec in 1740; it is possible that he had a son Pierre a year or so later, which would be the right age for the man who was Cree interpreter at Fort Carlton and died at the approximate age of 80 in 1821.93 The difference in ages suggests that Pierre was Martin Jr.'s grandfather, and that Martin Sr. died between Henry's departure (1812) and the consolidation of the fur trade companies in 1821. It is not unreasonable to suggest that there were three generations of Jeromes on the Saskatchewan after Francois, and that they must have had some connection with him.94

John Foster speculated that it was freemen of the 1770s and later, like Francois and Pierre, who married native women and gave birth to the young people who became the New Nation, the Metis of the Red River Valley. He argued that going en denuine to the Indian camps, marrying Native women, but still being outsiders led to the development of this separate identity.95 The only example he used was that of the Dumont family, whose descendant Gabriel became famous in the 1885 confrontation with the Canadian government.96 This was the first step in an intergenerational process of ethnogenesis. Language was also a good indicator of new ethnic identity. It probably took several decades for the in-group language of Michif (French nouns and Cree syntax) to develop in the buffalo hunters' camps, but I think that Foster would have agreed that this probably happened outside of Red River before 1815.

The Jerome family are thus a useful prototype of Metis ethnogenesis; by the third generation of French Canadian descendants living as Cree interpreters, they evolved a separate identity from the parent groups. They became the great horsemen and buffalo hunters, fluent in Cree and using Indian technology to survive on the plains and parkland. They were economically and psychologically independent, giving rise to the name by which they called themselves: gens libres or Freemen. They could support their families and hunt communally, sharing with their friends and relatives, while at the same time participating in the capitalist system of profit by trading their surplus dried meat and fat for pemmican to the fur trade companies, who were dependent on them for country produce to supply the canoe brigades to the northern fur fields. Although Ray suggested that the Plains Cree and Assiniboine became the provisioners in the Plains fur trade in the 1790s because the pedlars were taking the furs, it may be that the sons of mixed ancestry who travelled with the Cree bands and spoke Michif took over this function to make a profit rather than for subsistence.97

Foster identified the first step in the process, but he was only partly right. It was young men like Martin Jerome Jr. and his friend Jean Baptiste Letendre Jr. who developed the freemen culture and carved out their economic niche in the provisioning trade, separate from the Quebec traders and Plains Indians, which led to the development of the Metis. After the consolidation of 1821, when large numbers of these familes were no longer employed in the fur trade war, they moved to Red River, where they became the dominant group and claimed their birthright to the settlement of the North West.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Doug Fast. Geography Department,

University of Manitoba, for his cartography on maps 1 and 2. Any errors or

omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Notes

1. This research was funded by a fellowship from the Kavanaugh-La Verendrye Fund

at St. Paul's College, University of Manitoba.

2. "The Buffaloe" spelled with an "e" indicates a man rather than an animal. See

the family tree of Alexander Henry the Younger in Barry Gough (ed.). The Journal of Alexander Henry The Younger 1799-1814 (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1988),

xx.

3. Linguist John Crawford, one of the First linguists to study the Michif

language, also expressed amazement at the documented history of the Jerome

family in 2003 which was not available when he taught Jerome's sister at the

University of North Dakota Grand Forks in the 1980s. Personal communication,

September 20, 2003. See Crawford, "Speaking Michif in Four Metis Communities,"

Canadian Journal of Native Studies 3, no. 1 (1983): 47-53. Other

linguists

such

as Richard Rhodes, David Pentland and Peter Bakker have since expanded the study of this mixed language composed of French nouns and Cree verbs, the language of

the bison hunters.

4. Swan and Jerome, "The Collin Family at Thunder Bay: A Case Study of Metissage

," in David Pentland (ed.), Papers of the 19th Algonquian Conference

(Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 1998), 311—21. Swan and Jerome, "The History

of the Pembina Metis Cemetery: Inter-Ethnic Perspectives on a Sacred Site,"

Plains Anthropologist 4, no. 170 (1999): 81-94. Swan and Jerome, "Unequal

Justice: The Metis in O'Donoghue's Raid of 1871," Manitoba History 39

(Spring-Summer 2000): 24-38, Swan and Jerome, "A Mother and Father of Pembina: A NWC Voyageur Meets the Granddaughter of The Buffaloe," in John Nichols (ed.),

Actes du 32eme des Algonquinistes (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba,

2001), 527-51. Ruth Swan, "The Crucible: Pembina and the Origins of the Red

River Valley Metis" (Ph.D. dissertation. University of Manitoba, 2003).

5.Jacqueline Peterson, "Prelude to Red River: A Social Portrait of the Great

Lakes Metis," Ethnohistory 25, no. I (Winter: 1978): 41-67. Jacqueline

Peterson, "The People in Between: Indian-White Marriage and the Genesis of a

Metis Society and Culture in the Great Lakes Region, 1680-1830" (Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, 1981).

6. A.S. Morton, "La Verendrye: Commandant, Fur-trader, and Explorer,"

Canadian Historical Review (CHR) 9:284-98.

7. Jean Delanglez, "A Mirage: The Sea of the West," RHAFI. no. 2 (1947-

48): 541-68. Malcolm Lewis argued that the Sea of the West was not a myth, but a series of mistaken interpretations. See Lewis, "La Gande Riviere et Fleuve de

l'Ouest: The Realities and Reasons Behind a Major Mistake in the 18th Century

Geography of North America," Cartographica I (Spring 1991) 54-87.

8. Lawrence J. Burpee (ed.), Journals and Letters of Pierre Gauttier de

Varennes

de la Verendrye and his Sons (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1927). The search

for

the Western Sea is discussed in the biography by Yves Zoltvany, "Pierre,

Gaultier de Varennes et de la Verendrye," Dictionary of Canadian

Biography {DCB), vol. 3 (Quebec and Toronto: Universities of Laval and

Toronto, 1974), 247-54.

9. Nellis Crouse, "The Location of Fort Maurepas," CHRO (1928): 206-

22.

10. Gerald Friesen. The Canadian Prairies: A History (Toronto: University

of

Toronto Press, 1984), 53-54. A.J. Ray gives slightly different dates for the

establishment of these posts. See Ray, Indians in the Fur Trade (Toronto:

University of Toronto Press. 1974), 56. Figure 18.

11. Yves Zoltvany, DCB. on Pierre Gaultier, Sieur de la Verendrye, vol.

3. See also Kathryn Young and Gerald Friesen. "La Verendrye & the French Empire

in Western North America," in River Road: Essays on Manitoba and Prairie

History (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1996), 16.

12. Andre Vachon, "Antoine Adhemar de Saint-Martin," DCB, vol. 2

(Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969), 10-11. Jean-Guy Pellctier, "Jean

Baptiste Amable Adhemar," DCB, vol. 4: 5-8.

13. Rene Jette, Dictionnaire genealogique des families du Quebec des origines

a 173O (Montreal: Les Presses de l'Universite de Montreal, 1983), 598:

(Jerome dit Beaune, Leblanc et Latour, Francois, de ... Bretagne, 30 ans

en 1705; cited 18-11-1698 a Montreal; sergeant de la compagnie de Le Verrier."

C. Tanguay, Dictionnaire Genealogique des Families Canadiennes, vol. 2

(Montreal: 1887), 173: "Marriage of Francois Jerome Beaume, (father

of Francois Jr.) b. 1675, de St. Medrias, diocese de St. Malo [France]

and Angelique Dardenne, b. 1682, 3 novembre, 1705, Montreal." A footnote

suggests that his names are "Leblanc dit Latour, sergent de M.

Leverrier." On page 602 with the Jerome family genealogy, the footnote for

Francois Jerome suggests "Son vrai nom est Beaume." Sometimes, this name was

printed "Beaune" or "Bone." In the next generation, that surname was dropped and the son was known as "Francois Jerome dit Latour." Tanguay lists Jerome family

surnames: Baumeleblanc, Beaume, Beaumeleblanc, De la Tour, Latour, Leblanc,

Longtin, Patry, Riviere.

14.Jerome's first voyageur contract is recorded in the Archives Nationales du

Quebec (ANQ): "Francois Jerome dit Latour, 13 mai, 1727, Notaire: Jean Baptiste

Adhemar #3600."

15. See Hudson Bay Company Archives (HBCA) Search File, Gerome Family: Fort

Carlton District Report, B.27/C/2, fo. 2d, May 28, 1819. January 30, 1822:

"Samart Gerome and Battoches Son [Letendre] arrived from Dog Rump Creek's

House..." Martin Jerome was also known as "St. Martin Jerome" or "St. Matte

Jerome" after he moved to Red River Settlement in the 1820s; see for example

Census Returns, Red River Settlement (HBCA: E.5/2, #906, 1828 Census: St. Martin Jerome, age 28). This tradition was carried on in Red River by Martin's son,

Andre Jerome and his sons. Also, National Archives of Canada (NA), R.G. 15, v.

1505, General Index to Manitoba and NWT Half-Breeds and Original White Settlers, 1885: 8 children listed of Andre St. Mathe and Marguerite Gosselin, listed in

Ste. Agathe Parish. Public Notices of "Children of Half-breeds" also list the

children of Andre Jerome and Marguerite Gosselin as "St. Mathe" and "Martin

Jerome alias St. Math"; Provincial Archives of Manitiba (PAM), MG4 D13. In PAM,

MG2-B4-1: District of Assiniboia, General Quarterly Court: "Andre Jerome St.

Matthe, found not guilty on charge of levying war against the

Crown; charged 24 November, 1871." In Red River, the family was more commonly

known as "St. Mathe" than "Jerome" which can make it difficult to follow them in the records.

16. Tanguay, Dictionnaire Genealogique des Families Canadiennes, Jerome

Genealogy, p. 603. This volume includes Jerome entries to 1785.

17. Voyageur contract information is published in the Rapport de l'Archiviste de la Province de Quebec (RAPQ). The Detroit contracts were for Francois

Bone/Baune/Beaune. The complete name in the voyageur contract has been included

to show how Francois was identified in the records, as there is some variety.

But genealogical sources such as Tanguay and Jette suggest they were the same

person. His father Francois Sr. was too old to carry on this type of energetic

livelihood.

18. RAPQ, "Sea of the West" (1929-30), 429. In a report on "La Famille Jerome."

Alfred Forticr, Director of the St. Boniface Historical Society (SHSB),

mentioned that the Jerome family was present in the Canadian West for about 250

years, citing Francois's contract to sieur de la Verendrye in 1743 to look

for the Sea of the West. He also cited various North West Company (NWC)

references as in David Thompson, Masson and Alexander Henry the Younger to

Jeromes along the Saskatchewan River. Fortier began his Jerome Genealogy with

Martin Jerome Sr., married to Louise Amerindian, parents of Martin Jr. (born

about 1800) and Marie-Louise (born 1803), who moved to the Red River

Settlement in the 1820s. "La Famille Jerome," Bulletin, La Societe Historique

de Saint-Boniface 4 (ete 1993): 5. Edward Jerome had previously researched

this information when he brought the family to Fortier's attention.

19. RAPQ, "La Reine and Dauphin" (1922-23): 219-20. Clifford Wilson, "La

Verendrye Reaches the Saskatchewan," CHR 33, no. 1 (1952): 39-49.

20. Grouse disputes the location of this post, which may have been near the

mouth of the Red or on the Winnipeg River; "The Location of Fort Maurepas,"

CHR 9 (1928): 206-22.

21. RAPQ, "Maurrepas and La Reine" (1922-23): 238.

22. RAPQ, "Wabash" (1931-32): 237.

23. RAPQ, "Beaumayer to Michilimackinac" (1931-32): 352. St. Michel likewise,

same volume, p. 351.

24. Yves Zoltvany, "Pierre Gaulticr de Varennes et de La Verendlye," DCB,

vol. 3: 252.

25. Antoine Champagne, "Louis Joseph Gaultier de La Verendrye," DCB,

vol. 3: 242.

26. A.S. Morton, A History of the Canadian West to 1870-71 (London:

Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1939), 233: "In 1742-43, [ie Chevalier] and his brother

Francois made their final, if mistaken, attempt to reach the Sea of the West

with the assistance of the Gens des Chevaux."

27. Smith, G. Hubert, The Explorations of the La Verendryes in the Northern

Plains, 1738-43 (edited by Raymond Wood) (Lincoln: University of Nebraska

Press, 1980). Malcolm Lewis, "La Grande Riviere et Fleuve de l'Ouest: The

Realities and Reasons Behind a Major Mistake in the 18th Century Geography of

North America." Cartographica I (Spring 1991): 54-87.

28. Morton, A History of the Canadian West, 230-31.

29. Champagne, "Louis Joseph Gaulticr de La Verendrye." 241—44.

30. According to Antoine Champagne in his DCB biography of Louis Joseph

Gaultier de La Verendrye (Le Chevalier), (DCB, vOL. 3: 243-44), he was

active in the fur trade on Lake Superior. He went to Michilimackinac and Grand

Portage in the spring of 1750 to pay his men and obtain the furs to pay his

father's debts. In 1752, he was in charge of Chagouamigon (Ashland, Wisconsin)

on the southwest shore of Lake Superior. In 1756, he was made commandant of the

poste de l'Ouest and operated out of Michipicoten and Kaministiquia. He drowned

off the coast of Cape Breton in November 1762.

31. HBCA. A.11/114, fos. 130-131; York Factory Journal. May 17, 1749,

correspondence copied by John Newton, Master. Newton copied a translation

of Francois Jerome's letter into his journal. It is not the original in French,

but it is contemporary and documents his trading activity at Fort Bourbon.

32. Morton. A History of the Canadian West, 231.

33. Joan Craig, "John Newton," DCB, vol. 3: 482-83. Newton later

became famous as the composer of the hymn, "Amazing Grace," written after his

conversion to Christianity. Having been the captain of African slave ships, the

piece expressed his need for redemption.

34. A.J. Ray, Indians in the Fur Trade (Toronto: University of Toronto

Press, 1974), 89-91. Barbara Belyea, A Year Inland: The Journal of a Hudson's

Bay Company Winterer (Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2000).

Belyea compares four manuscript versions of Anthony Henday's journal, suggesting that there was another "original" source.

35. Note: Friesen erred in his naming of these forts. "Fort la Corne" was Fort

St. Louis, established by Louis Chaput, Chevalier de la Corne during the French

regime. He was made commandant of the Western Posts in 1753 and according to

Morton, "built a new post (possibly with 200 yards on the Fort LaJonquiere of

1751) on the Saskatchewan. It stood on the fine alluvial flat on which the HBC

built their Fort a la Corne towards the middle of the 19th. Century. Its remains

lie a mile west of the site of the Company's post. It was no more than an

outpost of Fort Paskoyac. Fort St. Louis, as La Corne's post was called, was

visited by Anthony Henday on his return." A.S. Morton, A History of the

Canadian West, 238. To clarify these names. Fort St. Louis was the French

name before 1763 and Fort a la Corne was the British name for the HBC post.

36. Gerald Friesen, The Canadian Prairies: A History (Toronto: University

of Toronto Press. 1984), 56. Although Henday did not give a name to the French

fort west of "basquea house," it was probably "Fort St. Louis" which was

established by Luc a la Corne. This name was later adopted by the HBC in

the 1800s in the same vicinity. See map in end of Dale Russell's Eighteenth

Century Western Cree and Their Neighbours, Archaeological Survery of Canada,

Mercury Scries Paper 143 (Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1991).

37. Belyea, A Year Inland, 188: E.2/U, May 29, 1755, on the return to

York.

38. A.J. Ray, Indians in the Fur Trade. 91.

39. Belyea, A Year Inland, 187: E.2/U, May 25, 1755.

40. Friesen, The Canadian Prairies, 56. He based this observation on the

comments of A.S. Morton who was critical of the HBC for not building interior

posts during the French regime. Morton saw the fur trade as a contest of

European empires, battling for territory: "True to Britain's form, it refused to prepare for the renewal of the crisis (competition with Montreal traders after

1763), and ... it had to develop its organization ... after the way had broken

out, slowly, painfully, and ... with great losses." A History of the Canadian

West, 251—52. For a discussion of the problems of editing the various

versions of Henday's journal, see Glyndwr Williams, "The Puzzle of Anthony

Henday's Journal," The Beaver 309 (Winter 1978): 41-56.

41. W.S. Wallace, The Pedlars from Quebec (Toronto: Ryerson, 1954),

13.

42. Many of these inland traders who travelled with the Cree returned with over

60 canoes full of furs and they succeeded in persuading some of the Blackfeet to trade at the Bay. Morton reported that some of the French traders were reckless

in their use of alcohol and were stealing native women which resulted in several attacks on their posts and several deaths. It may have been the fear of these

Indian attacks which inhibited HBC masters from building forts in the interior.

Morton, A History of the Canadian West, 252—53. Jennifer S.H. Brown made

the same argument in Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1980), 82.

Readers should be aware that Morton's opinions tended to be anti-French and

these

behaviours he ascribed to French Canadian voyageurs were shared by HBC men at

the bayside posts; for example, Joseph Hemmings Cook was accused of keeping

three Indian women under lock and key in his apartment at York Factory,

suggesting they were sex slaves (Charles Bourke, PAM, MG2AI: copy of Selkirk

Papers,v.67: 17868, May 1, 1812).The amount of abuse is difficult to estimate

because it was not well documented. It could also have been exaggerated as

voyageurs like Jean Baptiste Collin in Red River kept to one wife; see Swan and

Jerome: "A NWC Voyageur Meets the Daughter of The Buffaloe," Papers

of the Algonquian Conference (2001), 527-51.

43. See Clifford Wilson, "Anthony Henday" in DCB vol. 3 (1974), 285-87.

Henday was credited with being the first European to visit Alberta and see the

Rocky Mountains, but the latter claim is disputed by modern historians like

Glyndwyr Williams and Barbara Belyea. Because historians rely on documentary

evidence and most of French exploration was not documented, except for the La

Verendrye expeditions, their accomplishments are unknown. And the fact is that

all these outsiders depended on Indian guides who are usually invisible. Neither Henday's DCB biographer Wilson or A.J. Ray mentioned Henday's Cree guides,

Attickashish [Little Deer] and Connawappa. See Belyea, A Year Inland, 345

-46.

44. A.S. Morton. A History of the Canadian West, 254.

45. RAPQ (1931-32): 237, voyageur contract.

46. A.S. Morton, A History of the Canadian West, 254.

47. W.S. Wallace, The Pedlars from Quebec (Toronto: Ryerson, 1954), 7-10.

On May 16, 1769, William Pink from York Factory reported that he met the English Canadian trader James Finlay on the Saskatchewan and planned to take his furs

back to Montreal, but two men were left at the "lower house" to trade for the

winter. Thomas Corry came from Michilimackinac and wintered at Cedar Lake

below Pasquia, then took his furs to Grand Portage. Corry spent a second year on the Saskatchewan and then returned to Montreal, making such a fortune that he

was able to retire from the trade.

48. According to Antoine Champagne. Le Chevalier (Louis Joseph Gaultier de La

Verendrye) obtained permission in the the spring of 1750, after his father's

death, to go to Michilimackinac and Grand Portage, "to meet the canoes coming

from the west, in order to settle his father's business." He expected to be made commandant of the Western Posts, but did not receive the

appointment. In 1752, he was appointed to the post of Chegouamigon (Ashland,

Wisconsin, on the southwest shore of Lake Superior) to conduct the fur trade,

but conflicted with other French officers. In 1756, he was given commandant of

the paste de l'Ouest and remained in the Lake Superior area; the trade became

free and he had to buy the appointment. DCB, vol. 3: 243.

49. Charles Lart, "Fur Trade Returns, 1767," CHR3 (1922): 351-58. British

General Benjamen Roberts, Superintendant at Michillimackinac, wrote in 1767:

"This being the first year the traders were permitted to winter amongst the

Indians at their Villages and Hunting Grounds, it was fd. Necessary they

shid. Enter into fresh security with the Commissary, of this, the only post they had liberty to winter from, for it frequently hapned [sic] they made of (sic)

with their goods, by the Mississipi, and cheated the English Merchants, besides

they were restricted from trading with Nations that misbehaved." Presumably if

traders went west of this post before 1767, they were operating illegally i.e.

without the sanction of the British authorities in the Great Lakes. This illegal trade has not been documented to this point.

50. W.S. Wallace, "The Pedlars from Quebec." CHR 13 (1932): 388.

51. A.S. Morton, "Forrest Oakes, Charles Boyer, Joseph Fulton and Peter Pangman

in the North West, 1765-1793," Transactions Royal Society of Canada (

TRSC) 2 (1937), 89.

52. HBCA: York Factory Journal: B.239/a/56, William Pink's first expedition. May

16 and May 31, 1767. The Indians told Pink that the first house they passed had

been where the French resided 10 years earlier (in 1757) and a second site,

seven years earlier (1760). They predicted that "five large canews" would be

returning that summer or fall. This oral history suggests that French traders

continued to trade in the interior despite the British takeover in 1763.

53. Lart, "Fur Trade Returns," 353. Louis Menard would later be found as a free

trader out of the Brandon area trading goods to the Mandan on the Missouri, see

W. Raymond Wood and T.D. Thicssen. Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains

(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 43-44.

54. A.S. Morton. A History of the Canadian West, 268.

55. C. Tanguay, Dictionnaire Genealogique, "Jerome," 602-3.

56. August 7, 1767: "This Day Mr. Francis (La Blonc, a trader from

Michilimackinac) bound to the northwest, came in and brought some letters from

Major Rogers by which we understood we was to have no supplys this year from

him..." In John Parker (ed.), The Journals of Jonathan Carver (Saint

Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1976), 132. A footnote says that